Bancroft #

“The gems!” he shouted, the idea arriving like a gift from Sylvanus himself. If the statues had animated to protect the treasure, maybe they would chase it. And if the scorpions wanted to eat something, maybe they would settle for fighting stone instead of flesh.

He lunged for the second bowl on the altar, scooped it up, and hurled it at the scorpions. Stones scattered across the floor—mostly worthless glass and quartz that the tomb’s builders had mixed in to pad the offering, though a few genuine gems winked among the fakes: a dark bloodstone here, a pale carnelian there, bouncing and rolling between chitinous legs and stone feet. One of the barrow guardians swiveled its massive head, tracking the disturbance with whatever passed for awareness in its enchanted skull.

“Fine,” Bancroft muttered, grabbing the wooden vase from the center of the altar. “If gems won’t do it—” He hurled the vase at the nearest scorpion. It shattered against the creature’s carapace, shards of ancient wood spraying across the floor, and a single large gemstone rolled free from the wreckage, winking in the dying torchlight.

“Go!” Irulan shouted. “I’ll keep them busy!”

Bancroft didn’t argue. He saw the gap—a sliver of space between the nearest scorpion and the barrow guardian that had turned to track the scattered gems—and he ran for it. His shoulder caught the scorpion’s claw and he bounced sideways, stumbling, his plate armor scraping against chitin with a sound like a knife on a whetstone. He pushed through, ducking under the guardian’s reaching arm, his boots finding purchase on the ancient stone steps.

The entrance. He could see it—pale starlight filtering down from above, the promise of open air and escape. Three more steps. Two. One—

A hand of cold stone closed around his ankle.

The grip was crushing, inhuman, the fingers grinding against the steel of his greave with enough force to dent the metal. The barrow guardian from the crypt had followed him, emerging from a side passage he hadn’t even seen, and now it dragged him backward with the mechanical patience of something that had been doing this for a thousand years.

“No—!” Bancroft clawed at the steps, his gauntlets scraping furrows in the stone, but the guardian was stronger. The light of the entrance receded above him, inch by terrible inch.

Then Riyou’s arrow sang through the air from outside the barrow.

The shot was extraordinary—threading through the narrow entrance, past Bancroft’s flailing body, and burying itself in the guardian’s eye socket with a meaty crack. The stone figure staggered, its grip loosening for just a moment, one eye now a ruin of shattered obsidian and feathered shaft. But the fingers tightened again, dragging him deeper.

The struggle at the entrance became a contest of raw strength. Bancroft braced his free leg against the wall and pulled. The guardian pulled back. For a long, horrible moment, neither gave ground—Bancroft straining with everything his farmer’s body could muster against stone muscles that never tired and never weakened.

He lost.

The guardian wrenched him free of his handhold and dragged him back down into the darkness. Riyou fired again, another arrow finding its mark, but the guardian kept coming, kept pulling, its shattered face a mask of mindless purpose.

They ran. Behind them, the sounds of combat echoed from the barrow—the crash of stone against chitin, the wet crunch of a scorpion’s shell giving way—and then, mercifully, silence.

They returned the next day. It was foolish, probably, but the treasure still lay scattered across that chamber floor, and they were adventurers. Foolishness was part of the job description.

“Maybe they killed each other,” Bancroft said hopefully as they approached the barrow entrance.

They had not killed each other.

Two of the scorpions had survived, their chitinous armor scarred and cracked from the battle with the guardians, but their stingers still raised and their compound eyes still very much alive. The guardians, at least, lay in pieces—whatever magic had animated them finally spent.

Bancroft raised his holy symbol and prayed for light.

Nothing happened.

He tried again, reaching deeper, searching for the familiar warmth of Sylvanus’s blessing. Instead, he felt something cold and vast, like a winter wind blowing through the hollow spaces of his faith. The wood of his holy symbol cracked—a sharp, splintering sound that made Irulan flinch—and into Bancroft’s mind came not words, exactly, but understanding. A vision of darkness and corruption. A figure in black robes skulking near the main entrance to the barrowmaze. A Nergulite—a priest of the death god—poisoning the land that Sylvanus protected.

Kill it, the vision said, with the patient certainty of roots breaking stone. Kill the Nergulite, and my light will return to you.

Bancroft stared at his cracked holy symbol. “That’s… that’s new,” he managed.

“What happened?” Irulan asked, her sword already drawn, her eyes on the barrow entrance where the scorpions lurked.

“Sylvanus has given me a mission,” Bancroft said slowly, turning the damaged symbol over in his hands. “There’s a Nergulite near the dungeon entrance. A priest of the death god. Sylvanus wants it dead.”

Irulan and Seacrock exchanged a look.

“Well,” Seacrock said brightly, “that sounds like a problem for tomorrow. Tonight, I think we should discuss this over drinks. Many, many drinks.”

The Brazen Strumpet was packed that evening, as it always was when adventurers returned from the barrows with coins to spend and stories to tell. Seacrock made it his personal mission to ensure that Bancroft drank enough to forget Sylvanus’s holy directive, or at least to postpone thinking about it until morning.

“Another round!” Seacrock called to the barkeep, waving a hand with theatrical generosity. “My friend here has received a divine mission to go kill a death priest, and I think that calls for celebration!”

“That calls for preparation,” Irulan corrected, nursing her own mug with considerably more restraint. “Not pickling.”

“Preparation, pickling—they both start with P.” Seacrock pushed another tankard toward Bancroft. “Drink.”

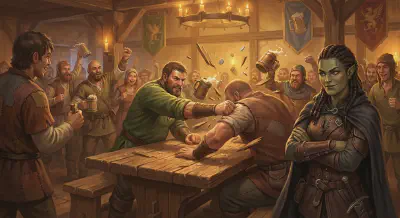

Bancroft drank. He drank rather a lot, in fact, which is how he ended up in an arm wrestling contest with a man twice his width and half his sense. The challenger was a caravan guard named something-or-other—Bancroft had stopped remembering names three tankards ago—who had been boasting about his exploits in voices loud enough to rattle the shutters.

“You?” The guard looked Bancroft up and down, taking in the farmer’s honest face and the callused hands that owed more to a plow than a sword. “You want to arm wrestle me?”

“I do,” Bancroft said, with the serene confidence of the profoundly drunk.

They clasped hands across a battered oak table. Someone counted to three. The guard strained, his face going red, the veins in his neck standing out like ropes. Bancroft simply pushed—and the man’s arm went down so fast, so hard, that the table shattered beneath them, mugs and coins scattering across the floor in a spray of splinters and ale.

The common room erupted in cheers.

“That’s two!” the barkeep called out, already nailing a plank to the wall beside the trophy from Bancroft’s nude footrace victory. “Bancroft Barleychaser—arm wrestling champion of the Brazen Strumpet! Drinks on the house!”

Bancroft beamed. This, at least, he understood. Not divine missions or death priests or cracking holy symbols. Just honest strength and the warm approval of good people.

Irulan, for her part, did not get drunk, and therefore had no fun at all. She spent the evening making sure Bancroft didn’t wander off to go fight the Nergulite in his cups, which was a full-time job.

None of them noticed Riyou slip away from the table early in the evening.

She was found later in a back alley off the market square, cornered by a fortuneteller—a woman with wild hair and wilder eyes who had seized Riyou’s wrist and wouldn’t let go.

“You have a destiny,” the woman hissed, her fingers tracing the lines of Riyou’s palm with feverish intensity. “I can see it. Written in your blood, in your bones. But you’ve been running from it.”

Riyou tried to pull free. The woman’s grip was iron.

“To achieve what you seek,” the fortuneteller continued, her voice dropping to a whisper, “you must become again what you once was. The marks you’ve covered—they are part of you. Denying them denies your power.”

When Riyou finally wrenched her hand free and stumbled back to the tavern, Bancroft noticed that her face was drawn and pale. He also noticed—couldn’t help but notice, even through the pleasant fog of ale—that her skin was marked with fresh tattoos, the ink still swollen and angry, layered carefully over much, much older ones that she had clearly gone to great trouble to hide.

She didn’t explain. Nobody asked. Some things, Bancroft had learned, were best left alone until the person carrying them was ready to set them down.

He ordered her an ale instead, and they sat together in comfortable silence, watching the fire burn low, each of them carrying their own burdens into the small hours of the night.